• First Australians

• First Australians

• Capatin Cook

|

Origins |

Captain Cook

Captain James Cook was born on 27th October 1728 in a two-roomed, mud-walled thatched cottage on the estate of Marton Hall in Middlesborough, North Yorkshire, England. His family later moved to Aireyholme Farm on the outskirts of Great Ayton where his father took up the position of manager. He attended the school in Great Ayton while working on the farm.

James was almost seventeen when he walked to Staithes to begin his first job, in the village general store. Eighteen months later a love of the sea drove him to the Port of Whitby and to an apprenticeship with John Walker on coal-carrying boats. |

|

In 1755 he made the momentous decision to volunteer for the Royal Navy. Europe was arming itself for what was to become the 'Seven Years War' (1756-63). Incredibly, only one week after signing up, Able Body Seaman James Cook's abilities were recognised and he was promoted to the position of Master's Mate on board the Eagle . After sorting out the tangled maze of square-rigging on the near derelict ship Cook was promoted to Boatswain (Bo's'n) and sent on the Eagle to patrol the Bay of Biscay for French ships. During the next two years Cook saw many sea battles and his skills did not go unnoticed. He was offered the position of Master, but apologetically turned it down, opting instead to attend the Naval Academy, where he gained his Master's certificate in 1757.

As a non-commissioned Warrant Officer, Master James Cook charted the St Lawrence River in 1759 and his excellent charts were a significant factor in enabling the British to take Quebec from the French. While on naval manoeuvres in Newfoundland he met a wealthy young traveller, Joseph Banks, who was later to bring him to the notice of powerful people. Cook married in 1762; he fathered five sons and one daughter, all of whom predeceased him.

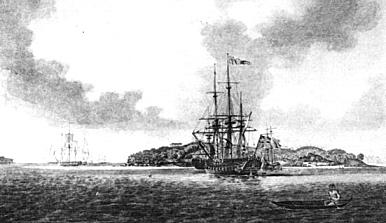

In May 1768 Cook was appointed by the Admiralty to command a converted Whitby 'coal cat', renamed the Endeavour Bark , to voyage to the Southern Hemisphere in order to observe the transit of the planet Venus across the sun and then to look for the rumoured South Pacific continent.

He set sail from Plymouth Steps in July 1768, rounded Cape Horn in April 1769, and recorded the transit of Venus in June 1769. That done he mapped New Zealand before crossing the Tasman Sea and sighting what would become Victoria on 19th April 1770. Heavy weather conditions prevented him from landing, so he sailed on until Sunday 29th April (ship's time) when he entered Botany Bay. |

|

“What Plymouth Rock is to America, so should this memorable spot on the south shore of Botany Bay be to Australians. Not since Columbus had such a discovery been made. Birthplace though it is of the great nation Australia is destined to be, it is comparitively little known, and certainly little reverenced.

The administrative methods of the early colonial authorities allowed this, above all places, to be one of the first to pass from the Crown into private hands.”

- From booklet of Immigration and Tourism Bureau, Kurnell Birthplace of Australian History, 1909 |

|

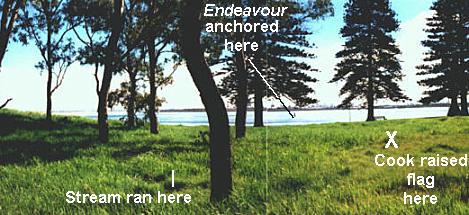

On Saturday 28th April 1770, Cook wrote: "At day light in the morning we discovered a Bay [Botany Bay] which appeared to be tollerably well sheltered from all winds and into which I resolved to go with the Ship and with this view sent the Master in the Pinnacle to sound the entrance while we kept turning up with the Ship haveing the wind right out". When Cook came to the heads of Botany Bay at 6am that morning it was low tide, and the Master sounded the entrance as the tide was rising. The tide was high when, as they ate their midday meal, they watched the Aborigines on the shore and fishing from their canoes in the bay. Joseph Banks wrote ".we soon saw about 10 people, who on our approach left the fire and retird to a little emminence where they could conveniently see our ship; soon after this two Canoes carrying 2 men each landed on the beach . the men hauled up their boats and went to their fellows upon the hill . We came to anchor abreast of a small village consisting of about 6 or 8 houses . an old woman followed by 3 children came out of the wood ... when she came to the houses 3 more younger children came out . four canoes came in from fishing, the people landed and hauld up their boats".

As two of the ship's boats approached the shore all but two of some thirty Aborigines who retreated to the bushes. Descendants of those Aborigines who lived at Kurnell and witnessed Cook's landing emphatically claim that their people did not run away and hide. Beryl Beller recalls: "When they saw a big white bird sailing into the Bay, that's what was handed down to me, they saw this big white bird coming, these two Aborigines went down as a warning party to let them get the children and hide them! They stood their ground and the others were [in the bushes as] a back-up to protect the family groups. On the rock stood two warriors, and there were about thirty marines. Two against thirty!"

Cook wrote in his journal: "I thought that they Beckon'd to us to come ashore; but in this we were Mistaken, for as soon as We put the Boat in they again Came to oppose us upon which I fir'd a Musquet between the 2 which had no other effect than to make them retire back where bundles of thier Darts lay & one of them took up a Stone & threw at us which caused my firing a Second Musquet load with small shott, & altho' some of the Shott struck the Man yet it had no other Effect than to make him lay hold of a Shield or Target to defend himself, immidiately after this we landed which we had no Sooner done than they throw'd 2 darts at us this obliged me to fire a third Shott soon after which they both made off." |

|

| Taking advantage of the now vacated beach Cook said: "Isaac, you shall land first!" Sixteen-year-old Isaac Smith, cousin of Cook's wife, clambered out to hold the boat for Lieutenant James Cook to land with dignity. This beach, Milgurrung Beach, was thus the birthplace of modern Australia. |

|

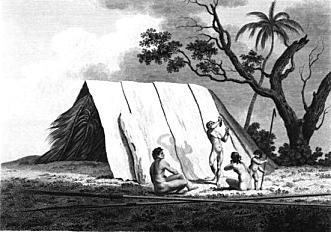

Cook notes that when his party landed on the shore they found "A few small hutts made of the bark of trees in one of which were four or five small children with whome we left some strings of beeds etc. A quantity of darts lay about the hutts these we took away with us."

These huts described by Cook were made by the age-old Aboriginal technique of ringbarking a stringybark or paperbark tree at ground level and again just below the branches. The bark was then split from top to bottom and the sheet levered off and manipulated over a fire to flatten it before being left two or three days to dry. It was then laid over a frame of tied saplings. The hut was lined with the fronds of the cabbagetree palm for greater insulation. "You can sleep in one of those huts in a storm and never get wet!" Beryl says. |

|

| "Three Canoes lay upon the beach the worst I think I ever saw, they were about 12 or 14 feet long made up of one piece of the bark of a tree drawn up or tied at each end and the middle kept open by means of pieces of sticks by way of thwarts". Fish were even cooked on open fires lit on a hearth of clay in these canoes |

|

Able seaman Forby Sutherland, who died of tuberculosis, was buried near the watering place on May 1st Cook named the point near his grave Point Sutherland. Sutherland was the first European to be buried in eastern Australia.

Joseph Banks recorded in his diary that each party of water-getters, grass cutters, wood gatherers and shooters from the Endeavour was closely observed by 12 to 15 armed natives. On one occasion ". 14 or 15 Indians having in their hands sticks that shone (say'd the Sergeant of marines) like a musquet. The officer on seeing them gathered his people together: the hay cutters coming to the main body appeard like a flight so the Indians pursued them . maybe a furlong." The following day two of Cook's men, who had gone ashore in Weeney Bay and walked back to the camp, were chased but not attacked by 22 noisy, armed natives. In the evenings, after Cook's men had returned to the ship, at least 11 canoes took to the waters of Botany Bay to catch fish, presumably because they had spent the day guarding their village. |

|

| The last full-blood Aboriginal chief of Kurnell, Cundlemong, who died in 1846 and was buried 50 metres from Sutherland's grave, said that the memory of Cook's landing was very much alive among his people. |

|

Cook eulogised Australia as a paradise. He wrote that the Aborigines ".may appear to some to be the most wretched people upon Earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholly unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary Conveniences so much sought after in Europe, they are happier in not knowing them. They live in a Tranquility which is not disturb'd by the Inequality of Conditions. The Earth and Sea of their own accord furnishes them with all things necessary for life, they covet not Magnificent House, Household-stuff &c, they live in a warm and fine Climate and enjoy a very wholesome Air, so that they have very little need of Clothing and this they seem to be very sencible of, for many of whom we gave Cloth &c to, left it carelessly upon the Sea beach and in the Woods as a thing they had no manner of use for. In short they seem'd to set no Value upon anything of their own for any one article we could offer them; this in my opinion argues that they think themselves provided with all the necessarys of life and that they have no superfluities."

In January 1967, an archaeological excavation of one of the many middens in the vicinity of Cook's landing place at Kurnell, near Cook's stream, revealed artifactsan axe, shell fish hooks, ironstone fish hook files, and mammal bone spear points. Well stratified in this midden was a simple bone button with a central perforation, a square-sectioned hand-made iron nail and a much-weathered portion of a glass rum bottle. Cook expressly mentions his gifts and, since carbon dating revealed the artifacts to be between 190 and 1330 years old, one may be confident that the midden was contemporary with the earliest period of white contact. The fact that these items were found in a midden buried beneath successive layers of shell preserved them. Middens were Aboriginal rubbish heaps. And according to Aborigines today, they would have just thrown those things away. "I don't think that if they threw spears at him [Cook] and got shot at, they would have valued them!"

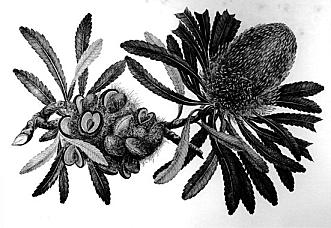

During the eight days they spent in Botany Bay, Joseph Banks and Swedish naturalist Dr Daniel Solander filled the great cabin (Cook's chart and navigational room) and much of the ship's hold with botanical specimens previously unknown in Europe. |

|

|

| In 1790 the Endeavour was decommissioned from the navy and bought by the French, who converted her into a whaling vessel. She put into Newport, Rhode Island USA, in September 1793 with a cargo of whale oil, seeking a safe haven during the war between France and England. There she stayed until in an attempt to move her she grounded on 30 th May 1794. By then she was rotten to the core. The Endeavour lay in Newport Harbour, disintegrating, till she was sold. The new owner dismantled her, abandoning the remains of the hull, which still lies on the bottom there. In 1996 the fragile rotten hull of the Endeavour was rediscovered in Newport Harbour and plans are currently under way to raise her. |

|

A piece of timber from the Endeavour and one of her cannon, raised from Endeavour Reef in near perfect condition, are to be found in the Discovery Centre at Kurnell.

Lieutenant James Cook's journal records that he saw, "The finest meadows in the world" around Botany Bay. It must have been an unusually good season. (Cook was promoted to Commander in August 1771, but he didn't officially become Captain until 1775 when he took over the Captaincy of Greenwich Hospital after he returned from his second voyage with the Resolution and the Adventure .) When Captain Arthur Phillip arrived eighteen years later with his miserable human cargo to found a convict colony, he anchored the 11 ships of the First Fleet off Bare Island on the northern side of the bay for 6 days. He had nothing kind to say about Cook's 'meadows'. According to Watkin Tench of Phillip's marines: ".we had reason to conclude the country more populace than Mr Cook thought it. For on the Supply's arrival in the bay on the 18th of the month [January, 1788] they were assembled on the beach of the south shore to the number of not less than forty persons, shouting and making many uncouth signs and gestures."

Phillip immediately wrote to Lord Sydney in London explaining that Botany Bay was unsuitable for a first settlement. Nevertheless he instructed Major Robert Ross and a squad of marines to begin building wharves, clearing campsites and sinking wells near the fresh water stream on Point Sutherland. He also ordered the digging of sawpits on the headland of Cape Solander. While that was being done (closely watched by muttering, gesticulating, armed and angry Aborigines), he took three boats to an inlet to the north, named Port Jackson by Cook but not entered by him. It is now world famous as Sydney Harbour. |

|

| On January 24 th , as Phillip was preparing to relocate the fleet to "the finest harbour in the world", two French ships were sighted attempting to enter the heads of Botany Bay. Phillip sent a boat to guide them in, while he hastily had the British colours hoisted on Point Sutherland and on all his ships to signal that Britain had claimed the territory. Thus, remarkably, this territory was only days short of perhaps becoming a French colony. |

| Top of Page |

|